On Oct. 31, 1980, a baby boy was born in Santiago, Chile, to a poor, young, Indigenous mother. He was whisked away before she was allowed to hold him, and later she was told that the baby had died. But, he was very much alive, taken away by a ring of traffickers who created fraudulent documents and sold him into international adoption. It would be decades before Jimmy L. Thyden González L’21, would discover the circumstances surrounding his birth and use his knowledge of the law to fight for the rights of thousands of other counterfeit adoptees around the world.

Amazingly, Thyden González’s story is not unique. Tens of thousands of babies had been victims of a scheme under Chile’s then dictator Augusto Pinochet, who believed that kidnapping the children of poor, Indigenous and often single women was a way to reduce the country’s poverty rate and improve economic conditions. His twisted rationale meant that the Chilean government would not have to support as many poor families, and, in turn, it would create an economic boom through fees paid by unwitting adoptive parents throughout Europe and North America. Corrupt doctors, judges, government officials and clergy were an integral part of running this horrific system of child trafficking, which, according to the Chilean government, took approximately 20,000 children away from their parents between the 1950s and 1990s. However, it is estimated by civil and nonprofit groups working to address the harms that the actual number is closer to 50,000.

Thyden González was adopted from a Chilean orphanage at age 2 by an American couple who had no idea that the child’s papers and backstory were fraudulent. They believed his birth mother had willingly given him up, being too young and poor to care for her baby. His paperwork called him “Carlos,” but the couple named him James “Jimmy” Thyden, and he had a happy childhood growing up in Virginia.

Taking A Closer Look at his Adoption Story

After high school, Thyden González joined the U.S. Marine Corps, where he served for 19 years. In 2011, just before he was preparing to be deployed to Afghanistan, his adoptive mother gave him his adoption records. As Thyden González looked through them, he began to notice discrepancies. One, for example, said he had been born in a hospital in Chile to a “known mother.” Another said he had “no living family.” Papers also indicated that his mother’s name was Maria González, which, unfortunately, was a very common name in that country. At the time, he had no idea what the real story was, but he put those thoughts in the back of his mind as he headed off to Afghanistan.

Upon his return, he often thought about investigating his adoption story, but he wasn’t quite sure how to begin. Many in his adopted family told him he was loved and that he should be grateful for the life he had been given, but he continued to feel a question that needed answering. Thyden González thought about traveling to Chile to research his background, but that required permission from the military and finances In addition, he spoke no Spanish and knew little of the culture.

Thyden González separated from the Marines in 2018 and earned an undergraduate degree from Liberty University, and then used the G.I. Bill and Syracuse’s commitment to the Yellow Ribbon Program to earn a law degree from the Syracuse University College of Law with the intention of being a criminal defense lawyer fighting the disparities toward people of color within the criminal justice system.

Making Connections to Find his Chilean Family

In 2023, his wife came across an article about a man who had been the victim of illegal adoption in Chile. The story felt very familiar to Thyden González, and he decided the time had come to find out more about the circumstances surrounding his birth and adoption. Notably within the article was mention of a nonprofit organization in Chile, Nos Buscamos, working to reunite families. An organization which he describes as “two ladies working with their laptops to change the world.”

Thyden González got in contact with them, eventually sending copies of his paperwork— and quickly learning that the attorney and social worker who had handled his adoption were some of the most notorious traffickers in Chile. He was advised to submit his DNA to MyHeritage, which had been supplying DNA kits to women in Chile in the hopes of finding some of the trafficked children. As a lawyer, he was hesitant at first, but, knowing there was the possibility of reuniting with his family, he finally decided to do so. Just 42 days later, the DNA results connected him with a woman from Chile identified as his mother’s cousin. He emailed the woman, who was herself skeptical but did tell him that there was a Maria González in her family and that she was alive.

Soon, he received a message from his aunt saying, “We found her, and she wants to meet you.” It was only after that that Thyden González first heard the true story of what had happened to him and his mamá on the day he was born, and how, since that day, she believed her son had died. Soon, he was frequently texting with his mamá in his “terrible Spanish,” as he raised the money to travel to Chile.

At the same time, González got in contact with other Chilean’s who had been illegally adopted, one of whom, Adrian Reamey, was making a documentary about the issue and wanted his legal expertise. She asked him to accompany her to Chile as part of the documentary-making process. Finally, he had the opportunity to reunite with his mamá and meet his family!

Reuniting With his Mamá

The reunion was tearful and overwhelming, as he hugged his mamá for the first time, surrounded by other relatives who welcomed him joyously. Thyden González, his wife and children, were able to spend a week getting to know his mamá. Soon after, he officially added “González” to his name, making him Jimmy L. Thyden González in honor of his Chilean heritage.

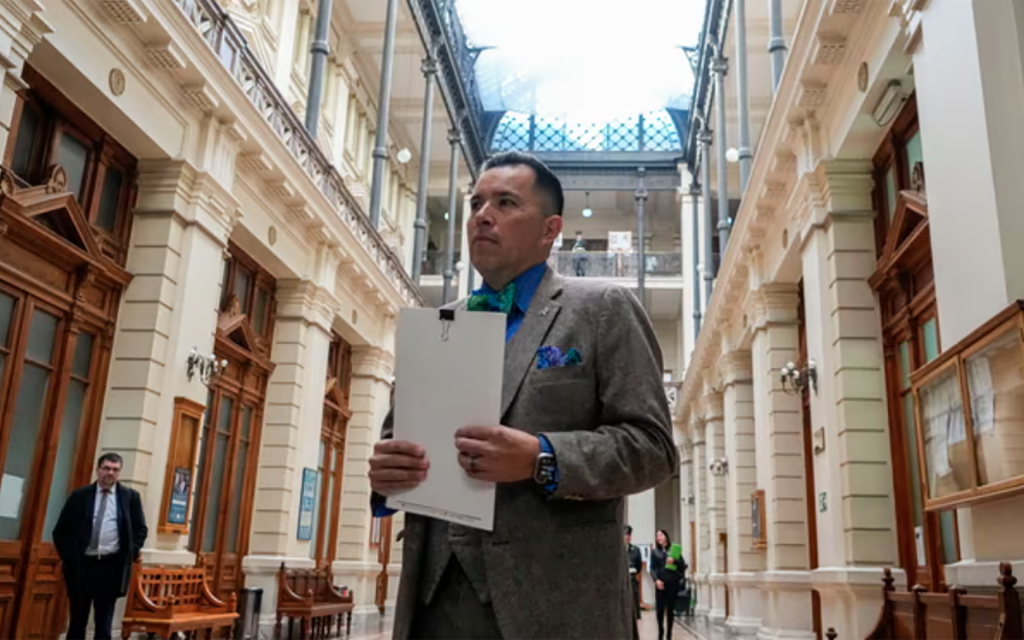

In the two weeks that followed, González stayed in Chile with the documentary film crew, meeting with government officials, where he learned that the Policia De Investigaciones De Chile (PDI), the civilian police department, had only five individuals in the entire country investigating illegal adoptions. No one was truly working to provide any kind of closure or reparations for the thousands of mamás and their stolen babies.

González returned to the U.S., put his law practice on hold and decided the best way he could help would be to get an LL.M. in international human rights, which he completed last year at American University’s Washington College of Law.

Creating a Nonprofit to Help Others Affected by Illegal Trafficking

At the same time, he created a nonprofit organization, Grafting Hope, to help those impacted by illegal human trafficking obtain reparations. The organization has already brought a great deal of awareness to these counterfeit adoptions, which, unfortunately, still continue at some level even today. Thyden González has met with officials in Chile and the U.S., making connections through both embassies. He also had the opportunity to brief the United Nations Committee on Enforced Disappearances, testifying on the atrocities of these illegal adoptions.

When he heard that the president of Chile, Gabriel Boric Font, planned a visit to the U.S., Thyden González started a grassroots effort through a group chat with other impacted adoptees asking them to come to Washington, D.C. Thyden González collected many of their stories with Nos Buscamos and Reamey and presented them to Boric, telling him, “These are our stories, and we need your help. We, too, are Chilean.”

Thyden González has since been working non-stop to make those impacted families whole again. In addition to Grafting Hope, he is collaborating with Chilean law firm Colombara Estategia Legal. Together he sued the Chilean government, fighting for reparations on the basis that it failed to protect these babies and their mothers, thereby violating their human rights. He has filed suit asking the Chilean government to acknowledge the harm caused and establish a commission to identify all victims, both mamás and children, as well as recognize the identity and citizenship of those stolen babies and their descendants. Thyden González himself cannot claim Chilean citizenship under his chosen identity since the name on his adoption papers was fraudulent. He also walks a fine line because unwinding his adoption might nullify his American citizenship with the chance that this retired, disabled U.S. Marine could be deported. But, if he can’t clarify his adoption and be cleared as an American citizen, it will be nearly impossible for him to bring his mamá and family to the U.S. to care for them.

Continuing to Create Awareness

Still, every day, he continues the fight, and his improved Spanish language skills have made it easier to keep in touch with his mamá. Thyden González recently published an op-ed in The New York Times telling his story and has been using various media outlets to continue to raise awareness of counterfeit adoption. Last November, he also shared his experience with students at Syracuse Law.

“It is not lost on me that I came to Syracuse Law to study criminal defense and was, in fact, the victim of a crime from the day I was born,” he says. “I intend to continue to advocate and fight, not only for myself and my mamá, but for every mamá out there who lost a child to this horrendous counterfeit adoption scheme. It has become my passion, and the center of my identity and my career. I don’t intend to stop until there is a resolution, but I also know it’s going to take time. Still, I hope to see that day come soon.”