by Shubha Ghosh, Crandall Melvin Professor of Law Director, Syracuse Intellectual Property Law Institute; Innovation Law Center

A contentious question in the field of intellectual property and technology commercialization is how broad a creator’s exclusive rights are in their work. Three current Supreme Court cases grapple with this issue in the fields of copyright, trademark, and patent.

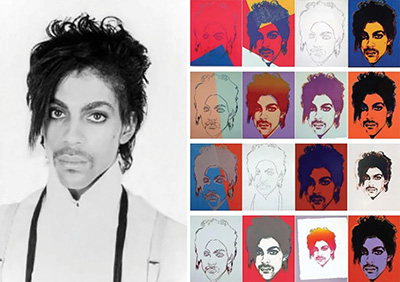

In Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, the trustee of the late artist’s estate claims the right to make 12 silkscreens based on Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of the late musical phenomenon Prince. Goldsmith had granted Vanity Fair the right to use her photograph of Prince, taken shortly after the release of his 1984 film Purple Rain, as part of a magazine article on the performer. Under the terms of the license from Goldsmith, Vanity Fair commissioned Andy Warhol to create artwork based on the photograph. Warhol copied the photograph as part of his silkscreen process to create Orange Prince, published in the 1984 Vanity Fair article. Warhol continued to make 12 more silkscreens from the photograph. These additional works came to light in 2016 after Prince’s death when Conde Nast, the publisher of Vanity Fair, released these twelve images in a tribute to the musician. Goldsmith complained to the publisher that these 12 silkscreens were unauthorized and infringed her copyright in the photograph. The Warhol Foundation initiated litigation to establish that Warhol’s creation of the 12 silkscreens was fair use and therefore allowed under copyright law. While the district court found in favor of Warhol’s Foundation, the appellate court disagreed, ruling that the silkscreens did not contain sufficient creativity to be a fair use of the copyrighted photograph. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments in October 2022, to resolve this dispute.

How broad are a copyright owner’s rights? Does Goldsmith’s copyright in her photograph allow her to prevent all copies or alterations of the image of Prince captured in her photograph? She authorized Warhol’s first silkscreen. Did the artist have to go back to Goldsmith to receive permission for each subsequent silkscreen? How about other artists who want to reproduce the Goldsmith photograph in their works or documentarians of Prince’s life who want to refer to the photograph in their movies? Does every conceivable use of the photograph have to be licensed or are there some uses that do not require a license because they are protected as fair use under the Copyright Act? The Supreme Court, as well as lower courts, have confronted questions like these for over one hundred and fifty years. Courts inform us that parody or other critical commentary are fair use. So are repurposing of copyrighted works to create new expressions, new uses, and new markets. For example, Google’s scanning of copyrighted books to allow a search that displays samples is fair use. In addition, copying of videogame software is allowed to create new platforms for playing games as is copying of smartphone software to allow new phone technologies, such as the Android. In Warhol, the Court seems poised to possibly expand fair use to encompass the creation of fine art that are not parodies or critical commentaries but embody original creative expression of an artist. How far the Court will go, we will see soon as its opinion should be out before June.

A portrait of Prince taken by Lynn Goldsmith (left) and 16 silk-screened images Andy Warhol created using the photo as a reference. Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Brands and trademarks are another set of legal rights whose boundaries are often tested. Jack Daniels found itself before the Supreme Court in March 2023, defending the use of its name and the design of its famed whiskey bottle against VIP, the manufacturer and distributor of dog toys. What caught the attention of Jack Daniels, particularly its trademark attorneys, was a squeeze toy marketed by VIP that mimicked a Jack Daniels bottle with the name Bad Spaniels on the label. Although the toy contained foam and no liquids of any kind, its label included statements about dog poop which some pet owners might find amusing. The district court found that the design of the bottle constituted trademark infringement as consumers might be confused into thinking that Jack Daniels had marketed the dog toy. The appellate court reversed, ruling that VIP’s toy was protected by the precedent of Rogers v. Grimaldi, a case from New York which allows the use of a trademark when the use does not denote authorship, sponsorship, or endorsement. The Rogers in this precedent was Ginger Rogers who sued Alberto Grimaldi, the producer of a movie called Fred and Ginger, a story of two dancers who emulated the famed duo. The New York federal appellate court ruled in favor of Grimaldi, and the court followed its own reasoning in ruling for VIP. The Supreme Court must decide whether to adopt the legal test in Rogers or adopt another approach to assess the uses of a company’s trademark in a humorous way on a product completely distinct from that of the trademark owner.

While my schedule conflicted with the oral argument for Warhol, I was able to attend the energetic oral argument in Jack Daniels. The Court rigorously grilled the advocates, who responded forcefully. The Justices, as a general impression, were concerned with the First Amendment problems in not allowing VIP to create its dog toy. Justice Kagan, however, questioned what VIP was trying to express by copying Jack Daniels’s trademark in this way. Acknowledging her recognized sense of humor, she questioned whether there was any parody here. Instead, she suggested the dog toy was just a knock-off (to use the vernacular, not her words) of the famed whiskey bottle. Justice Jackson, who asked the most persistent and penetrating questions, wondered if this was trademark infringement at all, as a matter of law, separate from any First Amendment concerns. After all, she pointed out, VIP was not branding its dog toys with Jack Daniels’ mark. The situation was different from the classic trademark case of someone selling a counterfeit Rolex watch. Finally, Justice Roberts, emphasizing the First Amendment concerns raised by his colleagues Justices Alito and Thomas, asked whether the Court needed to engage First Amendment law or work within the contours of trademark law to protect the speech interests of companies like VIP. The latter approach might entail adopting the lower court’s test from Rogers. Whatever approach the Justices take, the result, in my estimation, will not be unanimous and may well create an interesting opinion on how the First Amendment limits the scope of trademark rights.

Farther afield from photographs, fine art, whiskey bottles, and dog toys, is Amgen’s rights in the antibodies that constitute Repatha, the company’s patented cholesterol drug. The Supreme Court heard arguments a few days after the Jack Daniels dispute in a highly watched patent litigation between rival pharmaceutical companies Amgen and Sanofi. I was able to attend this oral argument as well and found the exchanges lively for what might appear to be a dry technical dispute. Once again at issue is how broad are the rights of the intellectual property owner.

Monoclonal antibodies, one particular type of antibody, are proteins that attach to cells and block them from invasion by pathogens, such as viruses or bacteria. Identifying antibodies and designing drugs around them are invaluable in treating diseases. Amgen identified 26 antibodies in its patent covering Repatha, an anti-cholesterol drug, but claims that this disclosure revealed 300 more antibodies. Therefore, the company argues, its patent covers a wide range of competing drugs, including Praluent discovered and manufactured by Sanofi. It may seem odd that Amgen is claiming rights not just in what it actually discovered but in other drugs that were made possible, or enabled, by its specific invention. At work is the patent doctrine of enablement which does allow a patent owner to claim a broad range of inventions beyond the specific discovery. A simple historical example illustrates this.

When Alexander Graham Bell made the first successful telephone call, it was to his assistant Thomas Watson in the next room. For patent law, a critical question is what specifically did Bell invent. It would be wrong to say that Bell invented an apparatus for speaking to someone in the next room. His invention encompassed more than that, allowing long distance communication. Specifically, Bell’s patent states that his invention consists of an “employment of a vibratory or undulatory current of electricity in contradistinction to a merely intermittent or pulsatory current, and of a method of, and apparatus for, producing electrical undulations upon the line-wire.” This technical language from the patent states what Bell invented. Anyone who makes or uses or sells a product containing this invention as described would be infringing Bell’s patent, which expired over a hundred years ago. This language shows what Bell’s invention enabled other inventors to do.

Patent law requires enablement for several reasons. Enablement provides notice to other inventors working in the field and to those who might want to license the patent. Enablement also makes sure that the inventor does not get more legal rights than is deserved. A patent rewards what an inventor has accomplished. An implication is that a patent owner might lose a patent if someone can show that the claimed invention has not actually been enabled. This is what happened in a famous Supreme Court case involving Thomas Edison.

Thomas Edison marketed a lightbulb using filament made from bamboo. A patent was issued to inventors William Sawyer and Albion Man covering light bulb filaments made of “carbonized fibrous materials.” The inventors sued Edison for patent infringement, claiming that the bamboo filament was an example of the carbonized fibrous materials. Edison successfully showed that Sawyer and Man had not actually invented a filament that could be made of any carbonized fibrous materials. Specifically, nothing in their work showed that bamboo, which Edison was able to make work after much effort, would serve as a light bulb filament. Therefore, Swayer and Man’s patent claim was found invalid and hence unenforceable.

Edison’s infringement woes are immortalized in the Incandescent Lamp Patent case, a Supreme Court precedent that is now being re-examined in Amgen v. Sanofi. Under this precedent, an inventor enables her patented invention if another inventor knowledgeable of the science can make the invention without too much experimentation. Edison had to work hard to show that bamboo would work as a light bulb filament contrary to Sawyer and Man’s claim that any carbonized fibrous material would work. Similarly, Sanofi is arguing that the antibodies that constitute its cholesterol-reducing drug were not enabled by Amgen. By contrast, Amgen is arguing that Sanofi’s antibodies would have been readily discovered without too much experimentation based on the antibodies that Amgen did discover. In other words, Amgen did enable Sanofi’s drug and therefore it infringes Amgen’s patent.

The dispute between Amgen and Sanofi has been proceeding for nearly a decade, with the lower courts ruling that Amgen had not enabled the antibodies in Sanofi’s drug. The Supreme Court will determine whether the lower courts reached the correct result. Readers may be justifiably skeptical that judges can work through such a technical dispute. Understandably, the Justices exhibited caution in questioning the attorneys arguing the various sides of the dispute. What informed the Justices was the policy over granting Amgen too broad a patent, one that would thwart a competitor, like Sanofi. Edison’s name was mentioned during the oral arguments. If Sawyer and Man had been successful in the patent suit, how would the light bulb have developed? If Amgen is successful now, what would be the impact on other inventors trying to compete in the pharmaceutical market? The Justices questioned Amgen to determine exactly how broad its patent might be. To be honest, in my opinion, Amgen’s attorney did not quell concerns that the patent might be too broad. At one point, he stated that Amgen may have enabled as many as 300 other antibodies and possibly even a million. Such a broad claim would have chilling effects on drug development. To be fair, perhaps Amgen has developed a blockbuster, game-changing drug, which would justify a broad patent. However, Amgen was not making a persuasive argument for how revolutionary its invention is, either in the lower courts or before the Supreme Court.

The trio of cases before the Court this term illustrates the importance of determining how broad intellectual property rights are for the commercialization of intellectual property and technology. How the Court decides these three cases will not settle long-standing and challenging legal problems but will fuel how attorneys work in the field. Recognizing these issues and keeping informed about how the law develops makes the practice of intellectual property and technology commercialization a constant source of excitement in guiding imaginative and entrepreneurial clients.

UPDATE

As this article went to press, the Supreme Court issued its opinions in the Warhol and Amgen cases on May 18, 2023 and in the Jack Daniels case on June 8, 2023. The Andy Warhol Foundation lost its appeal as the Court found that Orange Prince was very similar to Goldsmith’s Prince photograph and substituted for it in Vanity Fair Magazine. The Court split 7-2 with Justices Kagan and Roberts dissenting vehemently against the majority’s ruling that Warhol did not add creative transformation to Goldsmith’s photograph. Amgen also lost its appeal with the Court ruling that Amgen had failed to enable the antibodies that were the basis for Sanofi’s pharmaceutical. The ruling against Amgen ends that litigation. Finally, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of Jack Daniels, overturning the Second Circuit’s decision applying Rogers v Grimaldi to rule for VIP. Without much explanation, the Court held that Rogers, a case with applications to trademarks used in movie titles and song lyrics, had not application to VIP’s copying aspects of Jack Daniels’ trademark to brand dog toys. The dispute between the producer of whiskey and the purveyor of dog toys continues, perhaps to a settlement, perhaps to a trial.

Those interested in learning more about these opinions, please contact Professor Ghosh.